In the Introduction to the Jataka, or "birth stories" of the Buddha, it says that the Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree in powerful, one-pointed meditation, resisted the 10 armies of Mara, perceived the truth of things, and attained to full and un-excelled awakening. For those of you not familiar with standard Buddhist icons, Mara is the personification of the temptation of the world, the lord of all that is impermanent, simultaneously a satanic and trickster figure who does his very best to thwart those who would escape from his dominion and go beyond birth and death. During the heroic struggle of the Buddha on that day, he transforms and overcomes a great number of assaults by Mara and his armies through his steadiness on the Ten Perfections. The Ten Perfections can be translated a number of ways, and I list them as generosity, morality, renunciation, wisdom, energy, patience, truthfulness, resolute determination, loving-kindness, and equanimity.

These assaults by the Armies of Mara in the story are relatively fantastic, and while quite a mythologized and anthropomorphized bit of work still makes for fun reading. They consist of a whirlwind, a great rain-storm, showers of flaming rocks, weapons and hot ashes, sand, and mud, profound darkness, and a great discus hurled from a huge elephant. The Buddha was steady in his contemplation, deeply rooted in the Ten Perfections, having perfected his karma and mind for countless lifetimes before. Through the power of his actions and abilities, these assaults were transformed into flowers, celestial ointment, and the like.

Later on, the Ten Armies of Mara came to be listed as: 1) sensual pleasures, 2) discontent, 3) hunger and thirst, 4) craving, 5) sloth and torpor, 6) fear, 7) doubt, 8) conceit and ingratitude, 9) gain, renown, honor and falsely received fame, 10) self-exaltation and dispararaging others. These are now useful guidelines for difficulties that must be avoided when possible and seen as they are for meditators to progress on the path of wisdom. They tend to occur in roughly that order, cycling as does everything else. No eleventh army is listed.

However, it says in Sutta #26 of the Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha that soon after the Buddha's enlightenment, it occurred to him that there was no one else that could understand what he had understood. He thought to himself that this dharma was too profound, too subtle, too against the worldly tide, and too difficult. Teaching it would only cause him trouble, as it would be to a generation obsessed with lust and hate, mired in worldliness, incapable of understanding it, and so the Buddha decided to keep quiet.

There are other texts that say that it was Mara who came to the Buddha and said to him basically, "Alright, you win. You have gone beyond birth, death, and my realm. Who will understand what you have to teach? Who else can do this? Who will believe you? Nobody." The Buddha, as we have said, agreed without qualification. This I call the 11th Army of Mara, Mara's last temptation, the temptation to keep quiet. The 11th Army of Mara consists of the vast and profound difficulties those who are realized face in describing, explaining, and promoting real liberating insights.

The story continues in its typical style. The great Brahma Sahampati, a relatively high god, understood through his powerful mind that the Buddha had attained to full awakening and yet chosen silence and inaction. This was surprising considering that the Buddha had vowed to attain to that which was beyond birth and death so as to liberate all beings. The Brahma Sahampati appeared to the Buddha and begged him to teach the dharma so that those with little dust in their eyes might see. The story goes that he asked the Buddha to look at the world and see that there were in fact a few who would understand what he had to teach. The Buddha used his psychic powers to survey the world, and indeed he saw that he had been wrong, that there were a few who would understand, whose faculties were keen, whose eyes were only barely clouded. So, he wandered off in search of them and he found some of them. He taught them, they understood, and those teachings have been passed down in a direct line of practitioners that has lasted over 2,500 years.

While the ancient and modern commentators go to great lengths to rationalize why this was all part of the plan, that the Buddha just pretended to not want to teach for various reasons, I take a different, perhaps more cautious and probably realistic view. If we look at what happened as the Buddha tried to go and teach the dharma, we must admit that it was a long, difficult road. He had profound family problems, logistical problems, ran into bandits, had numerous conflicts with opposing sects as well as within his own order. People tried to kill him, his own order fractured at points because of extreme sects and views, people made power plays to take over the order, and so on and so forth. At one point he got so frustrated with his monks that he left them on their own for the whole three month rains retreat and went to be in the forest by himself.

Due to the continued bad and foolish behavior of his monks and nuns in the last 25 years of his teaching, he laid down the kind of restrictive rules usually reserved for vile dictatorships run by raving nut-cases. Clearly he did so reluctantly, as there were no such rules for the first 20 years of the order. The point here being that even for the Buddha, whose teaching ability was clearly of the rarest variety and who had an unduplicated knack for helpful and precise conceptual frameworks, there was nothing easy at all about spreading the dharma.

It is worth remembering that that however mythologized we feel the Buddha was, clearly he as a completely astounding person. He met his struggles with spectacular reserves of intellect, wisdom, stamina and determination. Few of us are so blessed, and the difficulties we face are largely the same as those faced by the Buddha.

I will now begin a short list of basic difficulties faced in trying to spread the dharma by those who know it for themselves. I list them in no particular order. The downside is that I have no great solutions to these problems, but as the AA kids say, admitting you have a problem is the first step.

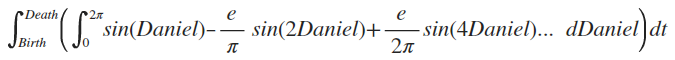

One of the most profound difficulties in supporting liberating insights is the difficulty in language. It simply cannot explain realization, though it can point to techniques that make it much more likely. Real insight goes beyond the conceptual frameworks of the dualistic mind. Anything you say about it is only partly true at best. The smarter the practitioner, the more frustrating they may find dharma language. The approximately 50% of adults who do not even have the capacity for formal abstract thinking will likely consider you very crazy, intimidating, or at best something to be avoided.

On a related note, if you actually are enlightened, then what is so glaringly obvious to you simply isn't to everybody else, and the longer you have seen it, the stranger it becomes that everyone else doesn't see it also. It can become harder and harder to remember what it was like to sit down on a cushion and not even be able to attain the first jhana, much less cycle effortlessly from the 4th to 16th ñanas. For those who have attained arahatship, the luminosity and centerlessness of perspective becomes such a natural part of one's perception that is seems incredible that it was ever otherwise.

On the flip side of the same coin, one may remember the profound struggles, the thousands of hours of back and knee pain, the extreme subtlety of perception needed, the endless stretching of one's perceptual thresholds, and the relentless determination and tolerance for pain and one's own humanity that was required to finally see it. We may remember the spent vacation time, financial difficulties, relationship issues, logistical complexities and difficulties with teachers and fellow meditators that are often necessary to endure for long retreats and extended daily practice. We may marvel that we were able to do it at all, much less imagine anyone else actually giving up all that they might have to give up and face all that they might have to face to do it. Are we really going to go around shaking people out of their cozy little lives for something we can't even explain?

That brings me to the question of audience. At any given time and place, there are only a handful at best that are ready to hear deep dharma and then convert that knowledge into liberating practice. This was true in the time of the Buddha and continues to be true today. Even among monks and nuns, you will not find many that are enlightened or even aspire to actually be enlightened in this lifetime.

Your best shot is those who have already crossed the Arising and Passing Away, though the complexities of the Dark Night can give them such a complex love-hate relationship to practice and dharma that you may not be able to reach them at all, or perhaps not until they have seasoned in it for years. You may never reach them, as they may not resonate with your personality, teaching style, or your own conceptual and linguistic baggage. You may not even be able to find them, though if you hang out some sort of shingle you will likely cross paths with at least a couple.

Meditation groups are flourishing around the country. You can find them in any mid-sized to larger city, and occasionally in more rural areas in more liberal parts of the country. And yet, very few of these people will actually take the time to get serious about meditation. In truth, few are interested in this at all. Most of these groups function essentially as sectarian churches, venues of social support with a unifying dogma and nice moral lessons, inspiring readings, sharing time, comfortable and satisfying rituals, a little meditation, and often overt or subtle worship and deification of Thich Nhat Hanh, Trungpa, the Dali Lama, Lama Zopa, or some other figure purported to have done it.

Very few will aspire to real mastery themselves. Very few will take the time to learn even the basics of meditation theory. Even fewer will actually go on retreats. Of those that do, only a handful will get their concentration strong enough to attain to basic jhanas or ñanas. Of these, only a couple will be able to cross the A&P, handle and investigate the Dark Night, attain to Equanimity and get Stream Entry. Of those who attain to Stream Entry, a reasonable number will progress to the middle paths, but not many will attain to Arahatship. Call me cynical, but this was true in the Buddha's time and it is true now.

You might think that you could approach these groups and say, "Hey, I know how it's done. Why read the dead books of some guy far away who you are unlikely to have any real contact with when there is someone right here who can help you understand it for yourself? Sure, you might have to bust your butt, but this is what you are all shootin' for, isn't it?"

Unfortunately, likely reactions include: complete disbelief, profound skepticism, confusion, alienation, intimidation, jealousy, anger, territoriality, competitiveness, and the lingering doubts created by having to face the fact that actually doing it is not what they are into at all. People hate feeling these things, and are more likely to blow you off than deal with these feelings. The chances of group or even an individual saying, "Great, I've been looking for a real friend in the dharma for years, and now there is one right here. Tell me how it's done and I'll go do it!" are essentially next to nothing. That said, miracles do occur, and occasionally we do actually run into the few who have little dust in their eyes.

If you are really into finding them, you are likely going to have to meet a lot of people who are not ready yet, even if you are lucky enough to teach at a major retreat center. This can be frustrating. If we look at the life of the Buddha, after the first dozen or so people he taught, he had to walk long distances to even find one person who might get what he was saying. Luckily, he was willing to do this.

How will we handle the 11th Army of Mara? Hopefully the Buddha's story will continue to inspire us to try harder.